Wills can be a cause of controversy: who’s in favour and who has been scorned? How is property distributed? The fascination of wills lies in what they say about people and their relationships. As Anne Mealia, a professional genealogist and historical researcher, told Hebden Bridge Local History Society, wills can bring family and social history to life. They contain details which fill in the gaps in family trees, often providing names across three generations and details of where people lived and how they made their living.

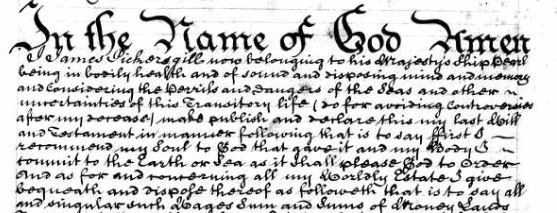

Even back in Anglo-Saxon times people wanted to ensure that they passed on property to the next generation, though these early wills were often spoken rather than written. By the Medieval period the dominance of the Church led to the process being formalised, encouraging people to make charitable bequests and pay for the prayers that might ensure a happy afterlife.

Not everybody made a will of course. Most people did not have much property to hand on or complicated affairs to resolve. Even in the 19th century only 20% of men made wills or had their goods assessed for probate. The proportion of women was even smaller, as a married woman’s property customarily belonged to her husband, so it was mainly unmarried or widowed women who were able to dispose of their own property through a will.

The nature of bequests raises questions, but context is important in proposing answers: why did Shakespeare choose to leave his second best bed to his wife? (Maybe she preferred it) Was Dickens being particularly unkind when he didn’t leave money to his estranged wife? (He had been paying her an allowance of £600 as well as paying for his children’s upbringing). In a will from 1761, Edward Pickersgill excluded his wife from benefiting, even removing the responsibility for the tuition of their children. Further research shows that his wife had been guilty of scandalous and immoral and behaviour and was living apart from him. Another testator made the risky decision to leave property to a daughter in law, excluding his own son, but this decision was a prudent one, since the son was bankrupt and all of the property could have gone to his creditors.

A man was supposed to ensure that his widow and his children would be cared for after his death, and widow would usually be entitled to live in the family home. After her death or remarriage it would pass to one or more of the children. There is a strong theme of keeping property within the family, and all kinds of complicated bequests were made to ensure equity in a father’s provision for his children. Sometimes bequests for a nominal amount of a shilling are made to someone who might otherwise dispute the fairness of a will. The existence of the tiny bequest showed that the omission of a larger legacy was not accidental.

If you are interested in finding family wills, discover more from the HBLHS website or join one of the regular drop-in Family History meetings at the Birchcliffe Centre.